What is Water Cooling?

Water cooling is the primary method that is used by internal combustion engines to dissipate heat, and it is the main alternative to air cooling. In a technical sense, water cooled engines are also air cooled. Although the waste heat from the engine is dissipated into a liquid coolant, the heat is then removed from the coolant via the cooling fins in a radiator. This is achieved by pumping the liquid coolant through the engine by means of a water pump. The liquid is channeled through coolant ports, hoses, and finally through a radiator. The main disadvantage of a water cooling system versus an air cooling system is the relative complexity, although they are also significantly more efficient.

Contents

History of Water Cooling

In the early days of water cooling, radiators were more or less expected to spew a geyser of boiling water under certain circumstances.

Like air cooling, the history of water cooling can be traced all the way back to the first days of the automobile. In fact, earlier steam engines also used water cooling to dissipate waste heat. However, technology that worked just fine with the relatively open cooling systems of external combustion steam engines didn’t translate very well to cooling internal combustion engines. Early water-cooled engines were plagued by a host of problems, and they were typically seen as less reliable than air-cooled engines.

During the period of time before WW2, water-cooled engines actually used straight water to dissipate heat. One of the main issues with using straight water was that the temperature of an internal combustion engine cooling system can easily surpass the boiling point of water. When that happens, the water starts turning into steam, the pressure in the system increases, and water is forcibly expelled from the cooling system.

This problem was exacerbated whenever a vehicle was under a heavy load, and anyone who drove over a mountain pass generally expected to have their water cooling system boil over and their engine overheat. To help ameliorate this situation, mountain roads were typically dotted with radiator filling stations and repair garages. Imagine having to deal with a constantly overheating engine, and expecting to have to refill your radiator every time you set off on a road trip, and it’s easy to see how air-cooled engines were so popular for so long.

Water Cooling and War

The widespread adoption of water cooling in the latter part of the 20th century can probably be traced back to the the second world war. As it started to become clear that the United States would eventually be drawn into the conflict, the US military started looking for new, reliable vehicles. This search resulted in the now-famous Willys-Overland Jeeps, but it also required solutions to the most serious issues with water cooling.

In order to improve the reliability of water-cooled engines, there were two problems that had to be solved: excess coolant loss and the tendency of these engines to boil over at altitude and under load. These closely related issues rendered water cooling unacceptably unreliable.

The solution to excess water loss was to improve the overall integrity of water cooling systems, which, at the time, had a nasty tendency to lose coolant without leaving any real signs of the loss. One of the major culprits was the way water pumps of the day were designed. These early water pumps were similar to those that had been used in steam engines, where water loss wasn’t much of an issue (since more water had to be added constantly anyway.) By improving the design of water pump seals, coolant loss during normal operation was greatly diminished.

The other issue that had to be solved was boiling over, and part of the solution to that lay in developing better antifreezes. Whereas early water cooling systems had used straight water, and antifreeze was only added during the winter, it was discovered that the addition of ethylene glycol reduced the boiling point of the coolant, while reducing the heat transfer qualities by an acceptable amount. Although ethylene glycol was first synthesized in the middle of the 19th century, and first entered commercial production in 1917, it wasn’t widely available as automotive coolant until WW2.

Water Cooling System Components

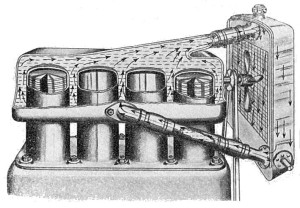

Modern water cooling systems use a pump to circulate the coolant through the engine and the radiator.

There are three components that every water cooling system has to include: a pump, hoses, and a heat exchanger. The pump drives the flow of the coolant through the engine, into the heat exchanger, and back into the engine, the hoses connect the engine and pump to the heat exchanger, and the heat exchanger actually dissipates the heat into the surrounding air. In common parlance, heat exchangers in water cooling systems are called radiators.

In practice, water cooling systems are typically more complicated. Most include a thermostat, which is a component that thermally regulates the flow of water through the system. This allows the engine to warm up by bypassing the radiator when the vehicle is first started up. After the engine has reached operating temperature, the thermostat opens up and allows coolant to flow through the radiator. If the thermostat sticks open, the engine will run too cool, which can lead to a variety of issues. If the thermostat sticks closed, the engine will typically overheat.

Most water cooling systems also include a heater core, which is essentially a second, smaller radiator. When coolant is channeled through the heater core, and a blower fan forces air through it, the resulting hot air can be used to heat the passenger compartment. This is one of the advantages of water cooling over air cooling, since vehicles with air-cooled engines have to use other methods to provide heat in the winter.

Liquid Coolants

A variety of liquids can by utilized by a water-cooled engine, from straight water to alcohol. Various mixtures of ethylene glycol and water were predominant for many years, although organic acid technology (OAT) antifreeze has become popular in recent years since it is somewhat less toxic. (According to DOW’s PSA on propylene glycol, it isn’t “acutely toxic” from a single, large dose.)

Water has excellent heat transfer qualities, but it also has a boiling point that is too low for effective use in the water cooling systems of internal combustion engines, and it can also freeze in cold weather (potentially causing catastrophic damage to an engine). Ethylene glycol has a higher boiling point and lower freezing point, but it doesn’t transfer heat as effectively. When water and ethylene glycol are combined, it is possible to achieve an acceptable combination of boiling point, freezing point, heat transfer qualities, and corrosion protection.