Automotive Air Conditioning is Cool

Automotive air conditioning systems use a handful of different methods to cool off the passenger compartments in cars, trucks, and other motor vehicles. They operate based on the same principles used by residential and commercial air conditioning systems, although they are specifically engineered to deal with the unique challenges involved in cooling down the interior of a moving vehicle. These systems have been available since the 1930s, although they didn’t really start to gain in popularity until the latter part of the 20th century.

We take automatic climate controls and A/C almost for granted today, but it wasn’t always so readily available.

Contents

History of Automotive Air Conditioning

Like many other options and accessories that would eventually be embraced by the OEMs, the issue of automotive air conditioning was first addressed by the aftermarket and hobbyist motorists. The first of these aftermarket solutions was installed in 1933. According to a Popular Science article that ran at the time, this system utilized a compressor that was similar to those found in refrigerators, which was mounted underneath the floorboards. Of course, these early automotive air conditioning systems were expensive enough that they were limited primarily to luxury vehicles.

The first OEM to offer an air conditioning package as optional equipment was the Packard Motor Company. Packard partnered with an aftermarket supplier of air conditioning units, to whom they would ship vehicles that had been ordered with the requisite package. After the air conditioning unit had been installed, the vehicle would subsequently be delivered to a local dealer. In a similar fashion, other OEMs would later offer to install aftermarket units at the dealership.

This 1940 Packard was the first car to offer an optional air condition package known as “The Bishop and Babcock Weather Conditioner”

Early air conditioning systems, like the “weather conditioner” offered by Packard in 1939, were unpopular for a handful of reasons. One issue was that the necessary equipment took up a lot of space. Whereas the first aftermarket units had been fitted underneath the floorboards, units like the weather conditioner were installed in the trunk, and they typically took up all of the available space. Even when they were installed in vehicles with larger trunks, the units were also unreliable and prohibitively expensive. (A base-model Packard Super Eight went for about $2,400 in 1939, and the air conditioning option was $274.)

Chrysler, Nash, and Climate Controls

Automotive air conditioning remained a relatively niche, unpopular option until OEMs like Chrysler and Nash started offering new options in the 1950s. Chrysler’s Airtemp, for example, added an air-recirculating feature, which filtered and circulated the air inside the passenger compartment. The Airtemp was also more efficient and powerful than earlier (and even contemporary) systems, in that it was billed as being able to cool off the interior of a roomy Chrysler Imperial from a scorching 120 degrees Fahrenheit to a relatively comfortable 85 in two minutes flat.

At around the same time, Nash introduced a front-end-mounted air conditioning system that included a few features that we still rely on today, such as an electric compressor clutch and dash controls to regulate the flow of cool air into the cabin. This was also the first fully integrated HVAC system available from an OEM, and it marked the first appearance of the type of automatic climate control system that would be recognizable to motorists today.

Widespread Adoption of Automotive Air Conditioning

Less than 10 years after Chrysler and Nash introduced their new technologies, roughly 20 percent of all new cars sold in the United States were equipped with air conditioning. In especially warm parts of the country, the adoption rate of the technology was already as high as 80 percent. These numbers would steadily climb, and by the end of the 1960s over half of the new vehicles in the US were being built with air conditioning. Today, it is standard equipment on a lot of new cars and trucks, although it remains optional on many lower-priced models.

How Does Automotive Air Conditioning Work?

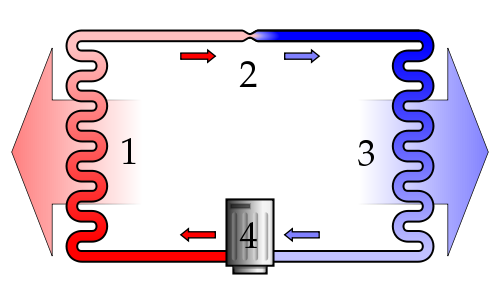

Today, automotive air conditioning systems operate based on the principle of evaporative cooling. These systems consist of six major elements:

- Compressor

- Condenser

- Evaporator

- Thermal expansion valve

- Drier/Accumulator

- Electric fan/Blower

- Refrigerant

In an evaporative cooling cycle, cooling is achieved by exploiting the fact that the refrigerant evaporates when it absorbs heat and condenses when it releases that heat. In order to achieve this, the refrigerant (R-12, R-134a, etc) is circulated through the system by a compressor, which itself is driven (via belt) by the engine’s crankshaft. When the low pressure refrigerant passes through the evaporator (which typically has a fan blowing through it), it evaporates and absorbs heat from the air that the fan is blowing. Accordingly, the air that then blows into the passenger compartment is cool.

After that, the evaporated refrigerant passes back into the engine compartment and through the condenser, which compresses it back into a liquid. This effectively releases the heat that was absorbed in the passenger compartment into the already-hot engine compartment.

Excellent synopsis! Cadillac joined the factory air ranks in 1941, along with Packard. What happened with auto air conditioning after the war and up to the Chrysler and Nash debut in 1953 and 1954 (and after)is covered in my book “Boy! That Air Feels Good!” A review is due out in December’s issue of Hemmings. Your readers ought to find it interesting. Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble and others.